The European Parliament drafted new rules last year to promote consumers' right to repair. A bold and timely move, according to professor of Law Alex Geert Castermans, but we’re not there yet. By Hans Wetzels

The European Parliament drafted new rules last year to promote consumers' right to repair. A bold and timely move, according to professor of Law Alex Geert Castermans, but we’re not there yet. By Hans Wetzels

The EU Right to Repair proposal has been adopted against a backdrop of growing environmental concerns, global warming, and a society that expects companies to keep a closer eye on how the impact of their business decisions and supply chains. ‘The right to repair is but one strategy that may alleviate the pressures on our natural environment’, Castermans says.

‘For decades, the right to return has protected consumers against aggressive sales tactics and poor product quality. Fortunately, there’s a growing realisation that a right to repair may be a more sustainable way of protecting consumers.’

Smart move

The aim of the new EU rules, is to introduce new legislation giving the consumer the right to have the products they purchased repaired. As the European Commission states in its press release: ‘Over the last decades, replacement has often been prioritised over repair whenever products become defective, and insufficient incentives have been given to consumers to repair their goods when the legal guarantee expires.’

‘There are many incentives for companies to tempt consumers into replacing a product’

According to Castermans, it may seem somewhat disappointing that the proposal only covers consumer rights. ‘But given the limited legal competence of the European Commission, I consider it a smart move. The Netherlands and the rest of the EU will be obligated to incorporate the new rules into their national judicial systems. ‘This is a good way to ensure that the right to repair will be implemented in a consistent manner in all member states.’

More sustainable consumer law

Once implemented, Castermans believes that the legislation may have a sizeable positive impact: ‘It is inherent to our society to buy ever more goods. We are taught to want new clothes as fashion trends change. This attitude deserves structural attention, but until now it has been proven difficult to address. I do feel the new right and duty to repair rules are a welcome move towards more sustainable consumer law.’

‘Mandatory repair may prove a great stimulant for a revival in European manufacturing’

Growth, competition and repair

There are, however, still some issues that need addressing. A key challenge for the newly proposed (and other) repair legislation is the prevailing economic paradigm that expects companies to continually grow while competing with others for market share. Castermans therefore expects businesses to try to water down the legislation. ‘There are many incentives for companies to tempt consumers into not making use of their right to repair, and to buy a new product instead. An especially weak point in the current legislation is that it doesn’t limit the time allowed for repair. Who wouldn’t opt for buying a new laptop if it takes three weeks for the old one to be repaired and returned? I also expect producers to pass the costs of the right to repair on to the consumers, by raising the prices of their products.’

Environmental impact

The proposed legislation could also have paid (even) more attention to the environmental impact. At the moment, if a product fails or malfunctions within the legal guarantee, the consumer may opt for repair or replacement, both free of charge. In everyday practice, free replacement is often chosen over free repair, with the defective but still viable item being thrown away. The new proposal explicitly prioritizes repair by making it obligatory – but only if the cost of repair is lower compared to replacing the product. ‘It is a purely financial assessment’, Castermans says. ‘The burden to the environment is still not taken into account.’

‘Who wouldn’t opt for buying a new laptop if it takes three weeks for the old one to be repaired and returned?’

Too much information

The proposal also tries to impose ways to make it easier for the consumer to have their products repaired when the warranty has expired. One of these is an information platform where consumers can compare the repair options offered by various producers. But researchers in the United States have calculated that reading all the information provided would completely overburden the consumers who want to make an informed choice regarding this matter. Castermans: ‘All in all, the Right to Repair proposal is a good start, but it certainly leaves plenty of room for improvement.’

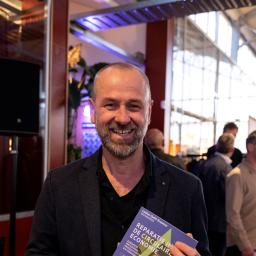

Alex Geert Castermans is professor in private Law at the Institute for Private Law of Leiden University since September 1, 2007. His research focuses on the interaction between European Law and Dutch private law, especially concerning themes such as global warming and corporate social responsibility.

This is an article from the white paper ‘Repair in the Circular Economy’, a joint publication of the Leiden-Delft-Erasmus Centre for Sustainability and the Faculty of Industrial Design, TU Delft. It has also been translated into English.