The housing shortage in the Netherlands amounts to more than 300,000 homes. At the same time, the quality of life is under pressure, particularly in vulnerable, superdiverse urban neighbourhoods. Hedy van den Berk, of the Havensteder housing association in Rotterdam, and researcher Reinout Kleinhans: 'Let’s reintroduce an extensive broad-based house building policy, so that teachers and nursing staff can also live in social housing.' By Maurice van Turnhout

In the political debate, the housing shortage is often directly linked to asylum and migration. Is that justified? Reinout Kleinhans, who is researching urban renewal at TU Delft: 'It is largely an image conjured up by politicians. Of the total number of migrants in the Netherlands, only 10-12 per cent are asylum seekers. But asylum reception problems are very visible, with the abuses at the registration centre in Ter Apel being widely reported in the media, and that obviously raises questions.'

'The number of migrant workers is significantly greater than that of asylum seekers. Most migrant workers doing low-paid work come to the Netherlands through an employment agency, involving arrangements that cover both housing and employment. They only get housing if they work here; if they lose their jobs, they are on the streets. These practices are particularly prevalent in the vulnerable, poorer, and older neighbourhoods of cities. The residents in these areas, who themselves struggle with the cost of living, can then see the downsides of migration only too clearly. That too reinforces their negative perceptions.'

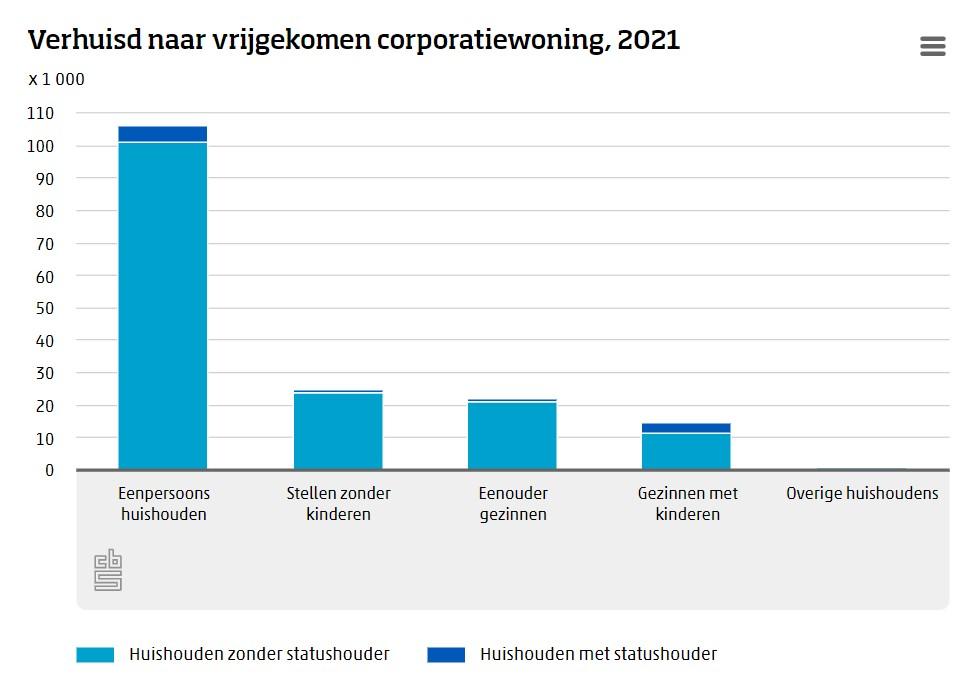

Hedy van den Berk, chair of the board of the Havensteder housing association in Rotterdam: 'Such malpractices mainly occur in neighbourhoods with a lot of private rental properties, where we as a housing association are less active. The percentage of social housing we allocate to asylum seekers who have been granted residence permits is quite low. But housing is scarce, people are on the waiting list for social housing for a long time, and they see certain groups of asylum seekers being given priority. That image of asylum seekers therefore definitely plays a role in this too. This increases levels of intolerance to newcomers.'

Hedy van den Berk, chair of the board of the Havensteder housing association in Rotterdam: 'Such malpractices mainly occur in neighbourhoods with a lot of private rental properties, where we as a housing association are less active. The percentage of social housing we allocate to asylum seekers who have been granted residence permits is quite low. But housing is scarce, people are on the waiting list for social housing for a long time, and they see certain groups of asylum seekers being given priority. That image of asylum seekers therefore definitely plays a role in this too. This increases levels of intolerance to newcomers.'

In many vulnerable neighbourhoods, tension is growing between different groups as they become more diverse. Why is that? Kleinhans: 'Carnisse in Rotterdam Zuid is a great example of such a superdiverse, but also vulnerable neighbourhood. If you look purely at the figures, it is a neighbourhood with a high degree of ‘fluidity’: the population turnover is unparalleled, with almost the entire population moving in and out every three or four years. This does not make community building any easier: the moment as people start to get on with their neighbours, they move away. This means that residents are less willing to invest their energies into their community.'

Is there anything that can be done about these tensions? Van den Berk: 'Housing associations can help promote greater tolerance in neighbourhoods by ensuring that residents do meet and do things together. This is only possible if housing associations are well represented in the neighbourhood. In Carnisse there are mostly private houses, but a few housing associations have gained a foothold and that immediately had a positive effect. There is now a diverse group of people active - both in terms of age and background - working on meeting places, playgrounds, or wall gardens that neighbours create and maintain together. As a corporation, you can help fuel that fire of community building. We put money and professional support into it but without wishing to take over: after all, they are residents’ initiatives.'

Local residents notice that differences with other people are not really bad at all.'

Kleinhans: 'I am reminded of Rotterdam initiatives such as the Wijkpaleis and the Nieuwe Banier. These are places where residents from diverse backgrounds are given a building to manage, by the local authority or housing association, in order to develop activities that meet a demand from the neighbourhood. Because of their small scale, there is no knock-on effect, but such initiatives can develop into hubs that bring many people together. Local residents then notice that differences with other people are not really bad at all, and indeed that they all face similar problems and challenges.'

We try to prevent slum landlords from buying up homes.'

Van den Berk: 'We are also trying to prevent slum landlords from buying up properties to house and then exploit migrant workers. We are doing this by increasing protection against mass purchases, such as in the Bospolder-Tussendijken district. This will make neighbourhoods more socially stable. By countering abuse and by supporting positive initiatives instead, we have noticed an increase in residents’ level of confidence. Existing tenants who were actually wishing to leave decide to stay, because they see their neighbourhood flourishing again.'

The Rotterdam Act allows the local authority to allocate housing in vulnerable neighbourhoods to relatively affluent households. Does that not put households with a migration background at a disadvantage? Kleinhans: 'From research, we know that discrimination according to migration background is widespread in the private rental sector. But even if you test for income in social renting, as with the Rotterdam Act, there are consequences. Precise figures are lacking, but the fact is that there is a strong correlation between migration background and low income in urban areas like Rotterdam Zuid. So there is a good chance that by doing so, you are discriminating against people from migrant backgrounds.'

We would like to prioritise people in essential occupations.'

Van den Berk: 'As a housing association, we implement the Rotterdam Act because we are obliged to. But the law represents a form of exclusion that we do not support. An alternative to this exclusion could be to prioritise people in essential occupations. In Rotterdam, for example, there is the priority scheme for teachers, and we implement it specifically in Rotterdam-Zuid. In fact, the main question is this: which group do you put at the back of the queue to allow others to move forward, and can you defend that? As far as we are concerned, at least, it is more justifiable than an income-based exclusion strategy.'

How can housing associations gain more clout to help improve vulnerable and diverse neighbourhoods? Van den Berk: 'Corporations exist mostly for the bottom end of social renting sector, as a safety net. Unfortunately, we lack the full range of tools to expand diversity. Associations perform services of general economic interest (SGEI), and their target group would ideally be widened to include, for example, middle-income earners. And both in terms of financial conditions and locations, it should become possible to build more, increasing tenants’ freedom of choice and the ability of housing associations to differentiate. That way, associations could be the constant factor in neighbourhoods throughout the economic cycle, and continue to invest when there is great demand for housing.'

Kleinhans: 'Until the 2008 financial crisis, urban housing associations had great scope to develop and innovate across the housing sector. That model of broad-based social housing, where social rental accommodation is available not only to the lowest income groups but also to middle-income earners, has been deliberately dismantled by politicians. The model gave associations the scope to house people in essential professions - such as teachers, nurses, and police officers - in cities. Politically, it is an illusion to think you can maintain total control of the migration society, but with more broad-based social housing, associations would have greater control of the vulnerable neighbourhoods in which that migration society is taking shape.'

Reinout Kleinhans is an associate professor of urban renewal at TU Delft. He contributes to the National Research Agenda Dilemmas of Diversity project and is co-author and editor-in-chief of the book De Migratiesamenleving (2022). He also researches online and offline civic participation, among other things.

Hedy van den Berk is chair of the board of the Havensteder housing association in Rotterdam. She is also chairman of De Vernieuwde Stad, a network of 25 metropolitan housing associations, a board member of the Nationaal Programma Rotterdam Zuid and chair of the Pijler Wonen consultation body.

White paper 'The migration city of then, now and later'

White paper 'The migration city of then, now and later'

This article is from the sixth white paper of Leiden-Delft-Erasmus Universities. If you would like to copy one or more texts, please contact Katja Hoiting k.hoiting@tudelft.nl.

Sender of this edition is the Leiden-Delft-Erasmus Centre Governance of Migration and Diversity, founded in 2020 to conduct interdisciplinary research on the governance issues surrounding migration, diversity and inequality.